Zachary Armstrong

Portraits

➝ Download Press Release

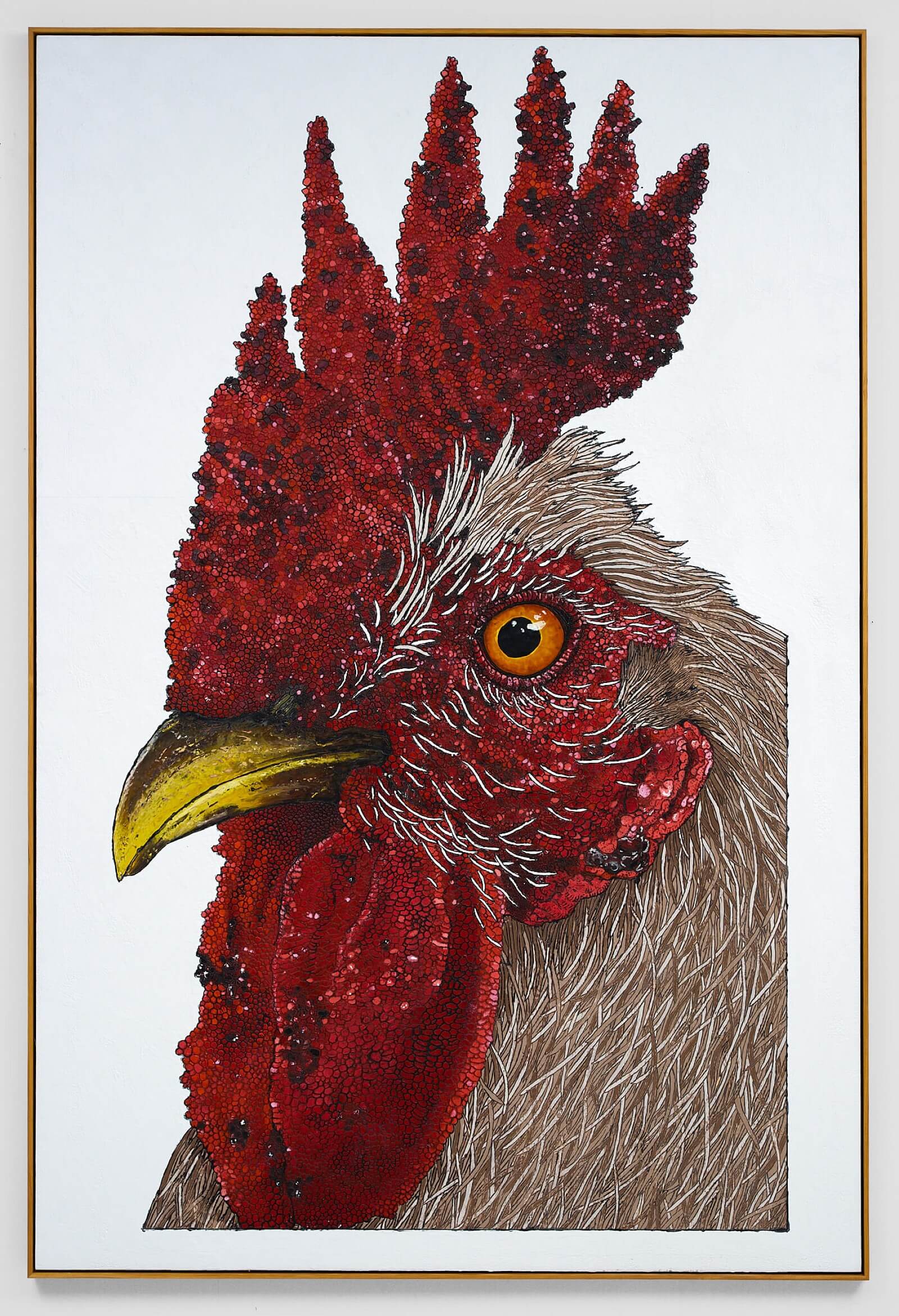

There is plenty of droll humor in Zachary Armstrong’s latest solo exhibition ‘Portraits’, which comprises more than a dozen vibrant, larger-than-life, encaustic paintings of roosters. Playing on our tendency to read ourselves into everything, and by gliding over the constructed distinction between human and animal, his portraits invite reflection on cocky displays of character and personality, and posit instances of interspecies cross-identification. Are these avian profile and three-quarter-turn head portraits really so different to those of beady-eyed, lace-necked merchants of the Dutch Golden Age, or the promotional filtered images of social media influencers on a pushed smartphone feed?

Roosters, of course, have a long and extremely varied cultural history as symbols including for the French nation, as a sign of the Chinese Zodiac, and of Ukrainian resistance. For Armstrong—who lives and works in the US mid-west and has an unabashed foible for Americana—the rooster may evoke the honesty of rural life. And thus by association, the benefits of early rising, the stoic farmyard, and the bustle of county fairs where proud breeders vying for ribbons and trophies present their livestock to judges. Armstrong’s fastidious renderings certainly suggest he loves his striking subjects with their fleshy red combs and silky plumage. The artist noted: “For years I’ve collected images of roosters from books, magazines, photos I’ve taken, google search, anywhere. When I first started working on this series of paintings, I was very particular about where the image came from. I would take an eye of a rooster from google search, a ‘comb’ (the top crown of the rooster) from a photo I’ve taken. I was collaging bits and pieces of different roosters to make a whole. I thought it was important that it was ‘my image’. About 2 or 3 roosters in, I realized that didn’t matter at all and that any good image would be great. Keep in mind not just any rooster photo would work. It had to be the perfect one.”* Jaded city-slickers might titter at his obsession with feathered friends. But how different is a county fair to an art fair? And who or what determines what is a ‘serious’ painterly subject? Meanwhile, Armstrong’s exhibition imagines the gallery as a raucous coup rather than as housing ‘a stable’. What better way to inaugurate a brand new gallery space—as this exhibition does—than with visual crowing! In real life, so many roosters gathered in one space would be impractical (if not downright dangerous). It is unclear if Armstrong’s intention is to evoke the pathos of cultivated hyper-masculinity, though it is in the room beginning with the obvious phallic pun involved. So forgive the observation that his gathering of decorative alpha-birds (like a group of macho board members or promotional portraits of artists from the 1980s) seems to point to the ridiculousness of the proposition that classical patriarchy is a viable or desirable norm for any species.

In fact though, Armstrong’s concerns have more to do with painting and process than gender discourse. And as for his choice of motif, followers of his work have come to expect the occasional aesthetic surprise. The stylistic variance in his work generally suggests it is primarily curiosity-driven. Crafty, it also evokes a hybridization of American Pop Art and folk art. In doing so, these works pit notions of appropriation, irony and ambivalence, surface-value and consumerist fetishization, against a kind of class-consciousness with moral tonalities that values the unpretentious, down-to-earth, authentic and handmade. Armstrong does not resolve this apparent duality, one that can also be experienced in the everyday. Instead, whether plotting abstract or zoological, he favors a strategy of complete immersion in his medium. The precision of his ‘built-up’ encaustic surfaces deploying pigment and oils suspended in wax, the result of endless quiet studio hours heating and forming, physically evidences the seriousness of his commitment to his image making. The artist explained his approach like this: “… once I started painting, I would have about forty different shades of red mixed up at any one time and once I finished a painting, I would trash those colors and start fresh. All that paint mixing is really what dictated what the rooster would end up looking like. A strange ‘Albers’ [Josef Albers, 1888—1976] thing started to happen, I would have a red that looked like fire engine red, bright red, I would paint areas with that, and then put what looked like an orange red down next to it, the fire engine red would immediately look brown, and the orange would look pink. It was crazy. I’ve never understood Albers until now […] the real beauty of knowing what those colors are doing, the change of them, only happens when he was painting them. During the process. Not on the wall later.” In this way, Armstrong’s series of bright cockerels speaks to: the idea of perceptive nuance; what we each choose to value or prize and why; and, the question of what company we like to keep.

Dominic Eichler